Briefing: 5th EU Road Safety Action Programme 2020-2030

2016 was the third consecutive poor year for road safety: 25,670 people lost their lives on EU roads compared to 26,200 the previous year – a 2% decrease. But this followed a 1% increase in 2015 and stagnation in 2014. In addition, around 135,000 people were seriously injured on European roads in 2014 according to European Commission estimates based on the MAIS 3+ standard definition of a serious injury.

Road collisions give rise to huge costs to society. A recent study estimated the value to society of preventing all reported collisions in the EU to be about 270 billion Euro in 2015, which is nearly twice as large as the annual EU budget.

Building political commitment and leadership at the highest level are prerequisites for preventing road traffic deaths and injuries. The lack of it at EU Member State level has contributed to a decline in levels of police enforcement, a failure to invest in safer infrastructure and limited action on tackling speed and drink driving in a number of countries. At the EU level, there has also been a conspicuous lack of action. This in turn has a negative influence at Member State level. Minimum EU vehicle safety standards have not been updated and plans to revise EU infrastructure safety rules have been delayed.

It is now time for the European Commission to build on the momentum and strong political will expressed by EU transport ministers in the Valletta Declaration on Road Safety[1] and come forward with a new and ambitious long-term road safety programme. The new EU 10-year action programme should be guided by the long-term Vision Zero[2] and embody the Safe System approach.[3] It should enshrine the targets adopted in the Valletta Declaration to reduce both deaths and serious injuries by 50% between 2020 and 2030. Alongside final outcome indicators, results-based performance indicators should be set.

The new EU 10-year action programme should also include priority measures for action and a detailed roadmap against which performance is measured and delivery made accountable to specific bodies. The programme should summarise the measures in different priority areas and how the tools fit together. A timetable should structure the main measures for adoption and implementation. It should also identify who the main players are to make sure that the desired future becomes a reality. The strategy must be set within the context of changing mobility patterns including new trends such as automation, increased walking and cycling due to promotion of active travel and the ageing of Europe’s population.

Road safety policy needs to be supported by effective institutional management in order to achieve long term effects on road safety levels. Clear institutional roles and responsibilities should be set up with strong political leadership from the Commissioner for Transport. As well as legislation, in the following decade the European Commission must continue to fulfil its crucial role in supporting EU Member States and motivating them to do their utmost.

Priorities for the next decade should be split between the need to continue work on reducing ‘traditional’ risks such as drink-driving, speed, distraction and failure to wear a seatbelt and tackling new and rapidly evolving challenges.

ETSC has identified nine main priorities for action with the top three outlined here in the Executive Summary: vulnerable road user safety, automation and reducing the numbers seriously injured on Europe’s roads.

A new, EU-level road transport agency could be critically important to planning and delivering new measures as well as providing regulatory oversight of the increasingly complex vehicle type approval that will be required to deal with increased automation.

Download

Improving the safety of vulnerable road users

Pedestrians killed represented 21% of all road deaths in 2014, the figure for cyclists stood at 8%. Powered two wheelers (PTWs) represent 17% of the total number of road deaths while accounting for only 2% of the total kilometres driven.[4] However big disparities exist between countries. [5] The share of deaths of unprotected road users is increasing as car occupants have been the main beneficiaries of improved vehicle safety. Cyclists and pedestrians are generally unprotected and are vulnerable in traffic. As active travel is being encouraged for health, environmental, congestion and other reasons[6], the safety of walking and cycling in particular must be addressed urgently.

Priorities for action in the next decade to improve the safety of pedestrians, cyclists and powered two wheelers fall under the three broad headings of infrastructure, vehicle safety and road user behaviour improvements.

Under infrastructure, ETSC would encourage the extension of the instruments of the Infrastructure Safety Directive to all EU co-financed roads and to main urban and main rural roads. Under vehicle safety, much more can be done and priorities should include redesigning car fronts to include cyclist protection (Regulation 2009/78) and introducing vehicle safety technologies which reduce prime risks: Intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA), Automated Emergency Braking (AEB) and alcohol interlocks. Front, side, and rear truck safety redesigns should be mandated to improve cyclist and pedestrian safety.

Within road user behaviour, enforcement should be intensified especially of speeding in urban areas where there are high numbers of pedestrians and cyclists.

Automated and connected mobility

How will regulators ensure autonomous systems are tested and approved to common standards, especially in a world where cars are already receiving over-the-air software updates that affect safety performance, such as Tesla’s autopilot updates? There is an urgent need to put in place certain prerequisites prior to the wider deployment of automated vehicles in Europe.

At present there is an urgent need for a new, harmonised regulatory framework for automated driving at EU level. Setting this up would be an essential precursor to automation. The EU type approval regime should be revised to ensure that automated vehicles comply with all the specific obligations and safety considerations of traffic law in different member states. This should cover all the new safety functions of automated vehicles, to the extent that an automated vehicle will pass a comprehensive test equivalent to a ‘driving test’. This should take into account high risk scenarios for occupants and interactions with cyclists, pedestrians and powered two wheelers.

While distraction might be mitigated in the long term by increased automation, urgent action will be required in the period to 2030 to reduce distracted driving in the existing vehicle fleet.

Serious injuries

Since 2010 the number of people seriously injured based on national definitions of serious injury on EU roads was reduced by just 0.5%, compared to a 19% decrease in the number of deaths in the same group of countries.[7] In 2014, around 135,000 people were seriously injured in the EU based on the common EU definition MAIS3+ according to estimates by the European Commission. There is strong political support to take action on serious injury.

Vulnerable road users, for example pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists or users in certain age groups, notably the elderly, are especially affected by serious road injuries[8]. Serious road traffic injuries occur on all kinds of road, but in comparison with deaths a larger proportion of them occur in urban areas and involve vulnerable road users[9]. On rural roads these injuries are more severe and thus more likely to be fatal.

Priority measures for reducing serious injuries include adopting an EU target which is monitored and regularly reviewed[10]. Infrastructure can also play a key role in reducing the severity of injury when collisions occur. Recommendations include drafting guidelines for promoting best practice in traffic calming measures and supporting area-wide urban safety management, in particular when 30km/h zones are introduced. One area for action is that of post-collision care. All European member states should offer equally high standards of rescue, hospital care and long-term rehabilitation following a road collision. Measures include involving health professionals in developing good practices and guidelines on essential trauma care and emergency services.

Download

Main recommendations

EU road safety strategy framework

- Prepare and adopt a new strategic Road Safety Programme for the EU including targets, vision, KPIs, measures and a timetable and structure for delivery.

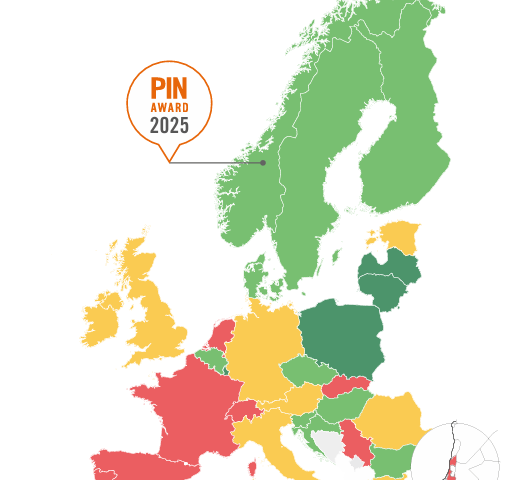

- Adopt measures to reduce the road safety gap between best and worst performing EU Member States, such as dedicated funds for infrastructure remedial schemes.

- Appoint a High Level Road Safety Ambassador and create a Road Safety Task Force.

- Introduce a new European Road Safety Agency which would fulfil a number of the following possible roles:

- collecting and analysing accident data and exposure data;

- helping to speed up developments in road safety;

- provide a catalyst for road safety information and data collection;

- encourage best practice across the EU;

- label unsafe roads, road equipment and vehicles;

- identify unsafe behaviours;

- communicate results to EU road users.

EU funds

- Identify funding within the new EU budget to support investment in new road safety measures and prevent the costs to society of road death and serious injury.

Vulnerable road users

- Dedicate funds for cycling, walking and powered two wheeler infrastructure under the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) to support increasing the safety of VRUs.

- Encourage EU Member States to adopt maximum 30km/h in residential areas and areas where there are high levels of cyclists and pedestrians, or where there could be potential to increase cycling and walking by investing in infrastructure.

Vehicle safety

- Upgrade type approval crash tests to be more closely aligned with the requirements of Euro NCAP crash tests.

- Redesign car fronts to include cyclist protection.

- Extend the mandatory fitment of advanced seat belt reminders as standard equipment to all seats.

- Fit all new commercial vehicles with assisting Intelligent Speed Assistance (the system should be overridable up to 90km/h for lorries, 100km/h for buses, in line with existing EU legislation on speed limiters, and 130km/h for vans) and all new passenger cars with an overridable Intelligent Speed Assistance system that defaults to being switched on.

- Ensure that retrofitting of vehicles with alcohol interlocks continues to be possible in the future. Legislate for a consistently high level of reliability of alcohol interlock devices. As a first step towards wider use of alcohol interlocks, legislate their use by professional drivers.

- Develop mandatory requirements for safer goods vehicles stipulating improved cabin design and underrun protection, and remove exemptions that exist so as to require the use of side guards to protect other road users in collisions with trucks.

- Develop a multi-phase, technology-neutral testing protocol for all M and N vehicles for distraction and drowsiness monitoring.

- Support EU Member States in collecting harmonised in-depth accident investigation data relating to fatal and serious injury collisions, including single-vehicle collisions.

Enforcement

- Create an EU fund to enable enforcement of speeding and drink driving using recognised best practices.[11]

- Evaluate the barriers preventing full implementation of the CBE Directive 2015/413 and adopt countermeasures to overcome them within the revision of the Directive.

Infrastructure

- Create an EU fund to support priority measures such as for cities to introduce 30 km/h zones (particularly in residential areas and where there are a high number of VRUs) and to invest in high risk roads which carry a high percentage of traffic.

- Extend the application of the instruments of the RISM Directive 2008/96 to cover all motorways, all EU (co-)financed roads, main rural and main urban roads.

- Set minimum road infrastructure safety requirements and draw up supporting technical guidelines concerning the harmonised management of high-risk sites by means of low cost measures.

Serious injuries and post-collision care

- Adopt a new joint EU strategy to tackle serious injuries involving all directorate generals in particular DG Health and Food Safety.

- Encourage Member States to develop effective emergency notification and collaboration between dispatch centres, fast transport of qualified medical and fire/rescue staff, liaison between services on scene, treatment and stabilisation of the casualty, and prompt rescue and removal to an appropriate health care facility.

Fitness to drive

- Propose a Directive on drink driving, setting a zero-tolerance level for all drivers.

- Introduce an EU zero tolerance system for illicit psychoactive drugs using the lowest limit of quantification that takes account of passive or accidental exposure.

- Apply the use of the classification and labelling of medicines that affect driving ability and support awareness information campaigns of medical professionals.

Child safety

- Under Directive 2005/39, make rear-facing child seats mandatory for as long as possible, preferably until the child is 4 years old.

Training and education

- Encourage all EU Member States to deliver road safety education that starts at school and which is part of a continuum of lifelong learning.

- Develop EU evaluation tools to design, implement and evaluate traffic and mobility education.

Novice road users (15-25 years old)

- Encourage EU Member States to push young people to use safer vehicles and utilise assistive technologies. Further explore the link between telematics-based insurance and safe driving.

Revision of EU Directive 2006/126 on driving licences:

- Introduce hazard perception training, expand formal training to cover driving and riding style as well as skills and encourage more accompanied driving to help gain experience.

- Develop minimum standards for driver training and traffic safety education with gradual alignment in the form, content and outcomes of driving courses across the EU.

Work-related road safety

Revision of Regulation 561/2006/EC concerning driving times and rest periods:

- Work towards consistent levels of enforcement of Driving and Resting time across the EU.

Support efforts to tackle fraudulent use of tachographs under Regulation 2014/165 including equipping enforcement officers with knowledge and equipment and improve use of data sharing arrangements between agencies within Member States.

- Extend the current legislative framework for professional driver training, driving and resting hours to van drivers.

[1] Valletta Declaration on Improving Road Safety. (2017), https://goo.gl/JsX7gS

[2] A vision can be regarded as a leverage point to generate and motivate change and needs to be far-reaching and long-term, looking well beyond what is immediately achievable. ETSC (2006) A Methodological Approach to national Road Safety Policies. Vision Zero was adopted in the European Commission Transport White Paper 2010, https://goo.gl/BwTY9R

[3] European Commission (2013) Commission Staff Working Document: On the Implementation of

Objective 6 of the European Commission’s Policy Orientations on Road Safety 2011-2020 – First Milestone Towards an Injury Strategy, https://goo.gl/gCw1zk

[4] ETSC (2011) 5th Road Safety PIN report, Chapter 2, Unprotected road users left behind in efforts to reduce road deaths, https://goo.gl/zxCfzx

[5] PIN Report “Making Walking and Cycling on Europe’s Roads Safer’ (2015), http://goo.gl/FVDAZW

[6] Geus, B.d. & Hendriksen, I. (2015), Cycling for Transport, physical activity and health: what about pedelecs? . In: Gerike, R. & Parkin, J. (red.), Cycling futures: From research into practice Ashgate Hendriksen, I. & Van Gijlswijk, R. (2010). Fietsen is groen, gezond en voordelig: Onderbouwing van 10 argumenten om te fietsen [Cycle use is green, healty and cheap: Evidence in support of 10 reasons to use bicycles] TNO Kwaliteit van Leven: Preventie en Zorg, Leiden, http://goo.gl/bCK3Vg

[7] It is not yet possible to compare the number of seriously injured between Member States because of the different national definitions of serious injury, together with differing levels of underreporting. It is also too early to use data based on MAIS 3+ for comparing countries performance over time. The comparison therefore takes as a starting point the changes in the numbers of seriously injured (national definition) since 2010.

[8] https://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/sites/roadsafety/files/injuries_study_2016.pdf

[9] European Commission (2013) Staff Working Document.

[10] https://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/sites/roadsafety/files/injuries_study_2016.pdf

[11] Several EU Member States have already successfully used EU funds to introduce safety camera networks.