New Driver Monitoring Requirements for Assisted Driving: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back?

When drivers use assisted driving systems like Tesla’s Autopilot, they are more likely to get distracted. New rules on driver monitoring for these systems are being voted on in Geneva this week as part of work on a major new regulation on driver assistance systems that will apply in Europe in the future. ETSC’s automation expert Frank Mütze takes a look at what’s at stake, and argues that the time limit for the system to act when a driver is distracted should be shorter.

New technical rules are being finalised for assisted driving systems such as Tesla’s Autopilot, Volvo’s Pilot Assist, and BMW’s Driving Assistant Professional. The legislation on DCAS ‘Driver Control Assistance Systems’ is being developed at the World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (WP.29) of the United Nation Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). A majority of the EU’s technical rules for vehicle systems are made there, in cooperation with countries outside of the EU and Europe.

Assisted driving systems automate part of the driving task, usually controlling a vehicle’s speed and keeping it in the centre of its lane. Unlike an automated driving system, the drivers remain responsible and are therefore ultimately in control.

Or at least they are supposed to be.

The assisted driving systems currently regulated for the European market have several shortcomings not least that drivers overestimate their capabilities and tend to over-rely on them, treating them as if they are automated driving systems that do not require human supervision.

In this briefing I will focus on the aspects of the new rules that are there to make sure drivers are not distracted and keep their attention on driving while using assisted driving systems. At ETSC, we are also satisfied with other improvements made through the DCAS regulation, yet remain concerned about other aspects, such as whether the system can be set to drive over the speed limit, or whether it should be allowed in the future to make lane changes by itself, but I will look at those in a future article.

First I will take a look at the risks of distracted driving while using assisted driving systems. I will then outline why the forthcoming rules could mean two steps forward, but one step back for road safety.

The Dangers of Distracted Driving

First a quick word on distraction in general. The European Commission recently published a report on distracted driving, showing that it is a significant risk factor. Although the exact number of crashes due to distracted driving is unknown, it is clear that it significantly increases the crash risk compared to attentive driving.

Phone use is a particular problem as eyes are off the road and at least one hand is off the steering wheel. Using a handheld phone while driving increases the crash risk dramatically, with a 12-fold increase in crash risk for dialling and a six-fold increase for reading and writing texts.

One key factor in the increased crash risk is the increase in time that the eyes are off the road. A naturalistic driving study from 2006 found that glances of more than two seconds for any purpose increase the near-crash/crash risk by at least two times compared to normal driving (Klauer et al, 2006).

Assisted Driving Promotes Distracted Driving

Following a two-year long investigation which encompassed multiple real-world crash investigations, the Dutch Safety Board’s 2019 report “Who is in control?” raised a number of questions about the safety of assisted driving systems. Among the issues raised by the report are human factor problems such as driver overestimation, misunderstanding and misuse as well as driver disengagement from the driving task.

This last issue should not have come as a surprise, as we have known for a while now that increasing the automation of the driving task results in drivers being increasingly prone to engage with non-driving related activities (Carsten et al, 2012).

It has furthermore been confirmed that assisted driving systems also increase the propensity of drivers to engage in non-driving related activities, both in studies and self-reported surveys (IIHS, 2022; supporting: Dunn et al, 2021; Noble et al, 2021; Reagan et al, 2021).

Dunn et al show that drivers with prior experience using assisted driving systems were almost twice as likely to be driving distracted when the assistance systems were active than during manual driving, while Reagan et al show that the longer drivers used assisted driving systems, the more likely they were to become disengaged, with a significant increase in the odds of observing participants with both hands off the steering wheel or manipulating a phone relative to manual control.

Assisted driving therefore “promotes” distracted driving and this underlines the need for a system that monitors what the driver is doing and warns them in case they are not paying attention to the road.

DCAS: The New Rules for Assisted Driving Systems

The new rules for assisted driving systems are being developed at the World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (WP.29) of the United Nation Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). A majority of the EU’s technical rules for vehicle systems are made there, in cooperation with countries outside of the EU and Europe.

Despite it being a World Forum, not all of its rules apply across the globe and in this case, the current and forthcoming rules on assisted driving systems are relevant for the EU, Russia and Japan, but do not apply in the USA or Canada.

In these new rules the assisted driving systems are referred to as ‘DCAS’, short for ‘Driver Control Assistance Systems’. These DCAS are a subset of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), and personally I always like to divide ADAS into two categories.

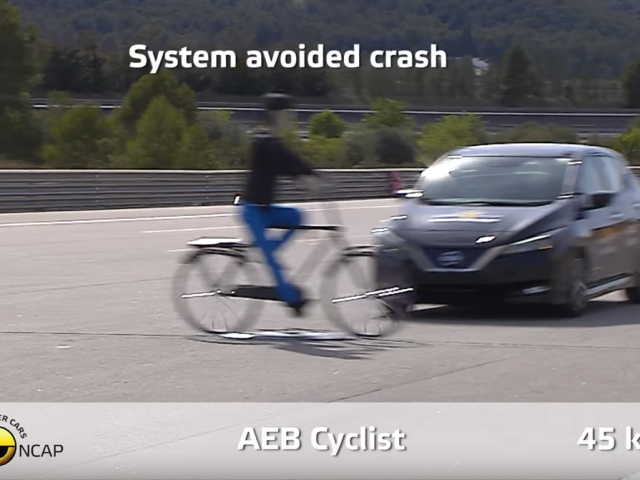

Firstly, the safety ADAS such as intelligent speed assistance (ISA), advanced emergency braking systems (AEBS), lane departure warning systems, electronic stability control, among many others that only intervene for a short period in the case of safety risks by providing a warning and/or controlling the vehicle in some way (e.g. AEBS automatically slamming on the brakes when it detects the risk of a potential collision).

Secondly, there are the ADAS that continuously control the vehicle’s speed and direction, not just in critical situations. It is still unclear whether these systems bring actual safety benefits (something which I will return to in a future article), and they are therefore often referred to as “driver comfort” systems. DCAS fall in this latter category.

The DCAS rules will (eventually) replace the current rules that allow assisted driving systems on European roads, which are set out in UN Regulation 79 on steering equipment.

When it comes to driver monitoring requirements, the new DCAS rules will be a significant improvement over the current rules in UN Regulation 79 as well as including an improvement over EU rules on driver distraction warning systems. But unfortunately, one element of the new rules will result in the overall package on driver monitoring not being as good as it could and should be.

Improvement #1: Visual and Manual Distraction Detection

The previously mentioned Dutch Safety Board report concluded that the current rules on assisted driving systems in UN Regulation 79 have some serious shortcomings, including weak provisions to make sure the driver stays attentive.

Currently, assisted driving systems only need to check whether the driver is holding the steering wheel. If the driver is not holding the steering wheel, the system should warn the driver with a visual warning at the latest after 15 seconds. If after 30 seconds (at most) the driver is still not holding the steering wheel, the visual warning should turn red and an acoustic warning should sound. Another 30 seconds without hands on the wheel would result in the system deactivating itself.

That means that the vehicle can drive without a driver holding the steering wheel for a minute – or for two kilometres when driving 120 km/h on a highway!

Making matters worse, the systems are easily tricked. In some cars, a driver intent on misusing the system only needs to apply a weight to the steering wheel to trick the system into thinking they are holding the steering wheel.

The following video (which features US vehicles and systems which are not identical to the ones sold in the EU) shows that most of those hands-on monitoring systems can also be used without a human in the driver seat. Granted, this is only possible when the driver is highly motivated to misuse the system, but it nevertheless underlines the weaknesses of the current rules on driver monitoring.

The new rules will improve driver monitoring in two ways.

The first improvement over the old rules is that a first warning should now be given not after 15 seconds, but 5 seconds–though this can be extended to 10 seconds if the system can confirm the driver is keeping their eyes on the road. If after another 10 seconds (instead of 30) the driver has not yet taken hold of the steering wheel, an acoustic warning should be given. This significantly reduces the time the driver can keep their hands off the steering wheel.

The second improvement is that the system shall now also monitor whether the driver is visually distracted. And given the importance for the driver to keep their gaze directed at the road, this is a significant step forward over the current rules.

It is of course not a bulletproof solution against distracted driving: there are still some question marks around the effectiveness of these systems (notably in relation to covering all variations in the population under different environmental conditions), the video above shows that they can also be tricked, and simply because having your eyes on the road doesn’t equate to having your mind with the driving task as well. But it is a promising improvement nonetheless.

Improvement #2: Distraction is not just about looking down

The second improvement of these new DCAS rules are not related to UN Regulation 79, but instead in comparison with the EU’s recent rules for ‘advanced driver distraction warning (ADDW)’ systems.

At ETSC, we have been pretty vocal that the current EU rules will offer precious little benefit. One of the reasons for that is that the system is only required to detect prolonged gazes towards the lap or feet, and not those toward the dashboard where infotainment touch screens are located, and where mobile phones are frequently mounted. When walking around the city, I also observe that distracted drivers often hold their phone at dashboard level as well, not always in their lap.

As such, the ADDW systems complying only with the minimum requirements set by the EU will be virtually useless as they won’t detect the most important types of distraction.

The positive news is that, in the future, cars fitted with DCAS systems will be required to detect whether the driver’s eye gaze and/or head position is directed away from any driving task-relevant area.

However, as infotainment screens nowadays are often also used to display ‘driving-related tasks’, this suggests that prolonged gazes in that direction could be exempted from the distraction warnings.

But as gazes longer than two seconds away from the road for any reason (including looking at driving task-related information) increases the crash risk, this would be undesirable. In any case if a driver needs to take their eyes off the road for more than two seconds to understand a system message or complete a driving related-task, that design is flawed and should be revised!

The problem with exempting the infotainment screens entirely is that there could be no warnings even in cases where the driver was distracted by things like apps, music controls and other infotainment functions.

ETSC therefore proposed that the dashboard area should not be considered as a driving task-relevant area. This suggestion was integrated into the regulatory text and should ensure that prolonged gazes away from the road and mirrors, for any reason including driving task-related, will trigger a warning.

Therefore, the types of distraction that the DCAS driver monitoring system should be able to detect is a significant improvement over the EU’s distraction system rules–and the European Commission should note this with a view to updating their requirements as well. The result would be a more effective distraction monitoring system for all cars, under all circumstances, not just DCAS-fitted cars while the DCAS system is in use.

One Step Back: Still Allowing for Distracted Driving

The new rules will allow the driver to take their eyes off the road for up to five seconds before a first warning is given – with a warning with increased intensity to be provided after an additional three seconds if the attention has not returned towards the road.

In comparison, the EU’s ADDW rules require a warning to be given after a maximum of 3.5 seconds – which in exceptional situations can be extended by an additional 1.5 seconds.

Here I should mention that the ADDW rules differentiate between two speed ranges, and that the 3.5 seconds limit applies to situations where the vehicle is traveling at speeds greater than 50km/h. When the vehicle speed is between 20 and 49 km/h, a maximum time of six seconds is applied.

This makes no sense from a road safety perspective. If anything, the duration for the speed range between 20 and 50 km/h should be shorter, as that speed range indicates driving in built-up areas where vulnerable road users are often present. Imagine driving at almost 50 km/h down a residential street with cyclists riding and children playing and shutting your eyes for six seconds!

I am also unconvinced by the reasoning for adopting the five-second time limit for DCAS, as this would be a simplification of the ADDW’s 3.5 seconds + 1.5 seconds. But those 1.5 extra seconds are meant for exceptional circumstances and this ‘simplification’ instead simply extends the time drivers can be distracted to five seconds in all circumstances.

As previously mentioned, we know from scientific research that any gaze away from the forward road (regardless of its purpose) longer than two seconds, at least doubles the crash risk.

By allowing the driver to be visually distracted for up to five seconds, the DCAS rules allow for the driver to take their eyes off the road for a period that is 2.5 times longer than what is considered safe. In those five seconds a lot can happen to which the driver needs to react, especially in dynamic urban environments where vulnerable road users are present.

In itself, the fact that the DCAS regulation allows for five seconds of distraction is bad enough. But what makes it worse is that the side-effect of assisted driving systems is that they encourage drivers to engage in non-driving related tasks and therefore to be distracted, as explained earlier.

Driver disengagement is recognised as a serious human factors problems for assisted driving systems, and driver monitoring systems are presented as the solution to this problem. But by allowing for such a long period before a warning is given, the previously mentioned two benefits are partially undone as one can only expect reduced effectiveness for its main task of preventing distraction.

I therefore hope that the countries voting on the new rules later this week will still reconsider revising the time limit down from five seconds to 3.5 seconds. Or better yet: set it at two seconds, in line with what is considered safe according to science.

As I mentioned earlier, while welcoming the improvements over the current situation, ETSC is also concerned about other aspects of the DCAS regulations, such as whether the system can be set to drive over the speed limit, or whether it should in the future be allowed to make lane changes by itself. I will look at those in a future article, so watch this space.