Response to the Public Consultation on the Future of the European Automotive Industry

The European Commission recently launched the strategic dialogue on the future of the European automotive industry. In response to the significant structural shifts the industry faces due to technological changes and competitive forces, the European Commission is currently engaging in a strategic dialogue with stakeholders, with the aim to identify the most critical challenges, potential solutions and roles, and to translate this into action.

As part of this strategic dialogue, the European Commission ran a public consultation to gather views on the main themes on which urgent action is needed. Several themes and topics had already been set out in the concept note prepared by the European Commission. ETSC’s response to the public consultation’s questionnaire is set out below.

To what extent do you agree that the themes as identified in the Concept paper for the Automotive Strategic Dialogue should figure in the EU industrial action plan for the automotive sector?

ETSC agreed that “innovation and leadership in future technologies and capabilities” as well as “regulatory streamlining and process optimisation” should be included in the EU industrial action plan for the automotive sector. Based on the descriptions provided in the concept note, ETSC expressed no opinion on “clean transition and decarbonisation”, “competitiveness and resilience”, and “trade relations and international level playing field”, given that these were unrelated to road safety.

Are there additional themes that should be added to the upcoming EU industrial action plan for the automotive sector? If so, please list them with a short explanation why.

Safe automotive mobility should be added as a theme. At least 85% of the 20,594 persons killed on EU roads in 2022 were due to collisions involving passenger cars, vans, trucks and/or buses. In order to achieve the EU’s goal to reduce road deaths to zero by 2050 and given the stagnation in the reduction of road deaths, more should be done to improve road safety, including through increasing the safety of motor vehicles.

As the impact assessment for the revised General Safety Regulation for motor vehicles states in greater detail, the relative international competitiveness of EU based production can be aided by the first mover advantage of EU automotive suppliers in the vehicle safety equipment market, by the knock-on effect of increased safety reputation of EU vehicle brands, by allowing for economies of scale of vehicle safety equipment producers leading to lower unit cost, and by the ability to set world standards by means of introduction of new EU vehicle safety legislation and its global harmonisation potential (e.g. through UNECE cooperation with non-EU contracting parties). Clear examples of this last point are the ongoing processes at UNECE, initiated by Australia, to establish UN Regulations on the emergency lane keeping system, the driver drowsiness and attention warning system, and the advanced driver distraction warning system, which all take the EU requirements as their basis.

Improving vehicle safety by updating the EU’s General Safety Regulation for motor vehicles – which is scheduled for review in 2027 – therefore not only presents an opportunity to improve road safety, but also presents opportunities for the automotive industry’s competitiveness and innovation.

Just as the automotive industry is being challenged, so is Europe’s approach to tackling road safety in trouble. There were 20,400 road deaths in the EU in 2023 – down just 1% on the previous year. While this is a 10% reduction since 2019 – the baseline for the 2030 target of halving road deaths in the EU – the downward trend has flat-lined in several Member States and risen in others. At European level, there is an urgent need for strong leadership and action on road safety to get things back on track. Vehicle safety – where the EU has the exclusive competence – is an important pillar of the safe system approach to improve road safety and additional actions are desperately needed. This in addition to further efforts to make road users and the infrastructure safer, as well as to enhance enforcement and post-crash response. (More information on the road safety priorities for the EU’s 2024-2029 mandate is available here.)

Do you have any other comments or remarks as regards the EU industrial action plan for the automotive sector?

Specific items mentioned in the Concept Note present both opportunities to improve road safety as well as risks to worsen it.

Autonomous driving has for example the potential to improve road safety significantly. However, this potential will only materialise if and when a robust regulatory framework is in place. Rushing automated driving to the market will risk worsening road safety if done without stringent type approval requirements in place to ensure those vehicles are safe before entering the road, and without an EU-level system in place to monitor the safety of automated vehicles while on the road. The strategic dialogue should therefore discuss the establishment of an EU Agency for Road Transport, which among others should be tasked with type approval as well as monitoring duties. In the framework of monitoring the safety of automated vehicles, such Agency should be granted powers to independently carry out and coordinate crash investigations.

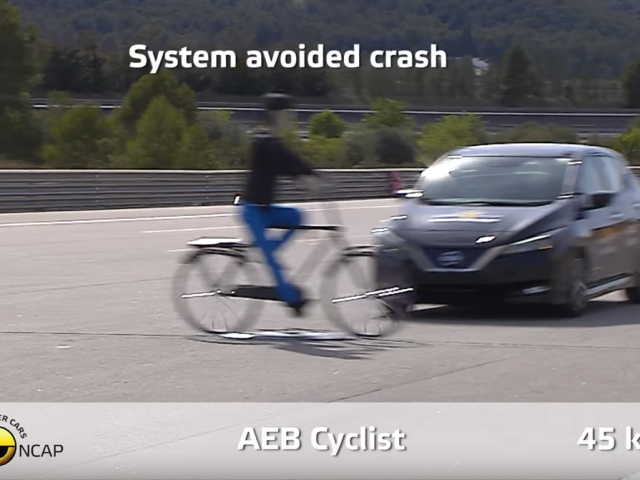

In a similar vein, the “safety regulation for advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS)” mentioned in the concept note should focus on those ADAS that have a demonstrated potential to improve road safety. The use of so-called “Level 2” ADAS for which no such safety-improving evidence is available should remain restricted, especially as they have shown to lead to drivers confusing them for automated driving systems and as drivers have shown to over-rely on them. The previously mentioned EU Agency for Road Transport should also be tasked with monitoring the safety of such “Level 2” ADAS (and DCAS in particular), and be granted the power to independently investigate crashes involving vehicles with such systems.

A regulatory streamlining activity should also review the conflict between safety and data protection in the case of event data recorders (EDR). The original purpose of requiring EDRs in new vehicles was to provide a data source to help prevent future crashes. However, due to the data protection provisions included in the General Safety Regulation for motor vehicles, the EDRs are currently prohibited from recording data on time and location. The result is that EDR data by itself is virtually useless to road safety researchers, as those data points on time and location are vital for determining the circumstances of a collision. For example, without location data it is impossible to tell based on the EDR-recorded speed data whether the vehicle was travelling at an appropriate or inappropriate speed, as the relevant road – and therefore the applicable speed limit – would not be traceable.